Popular Locations

- Yale New Haven Children's Hospital

- Yale New Haven Hospital - York Street Campus

- Yale New Haven Hospital - Saint Raphael Campus

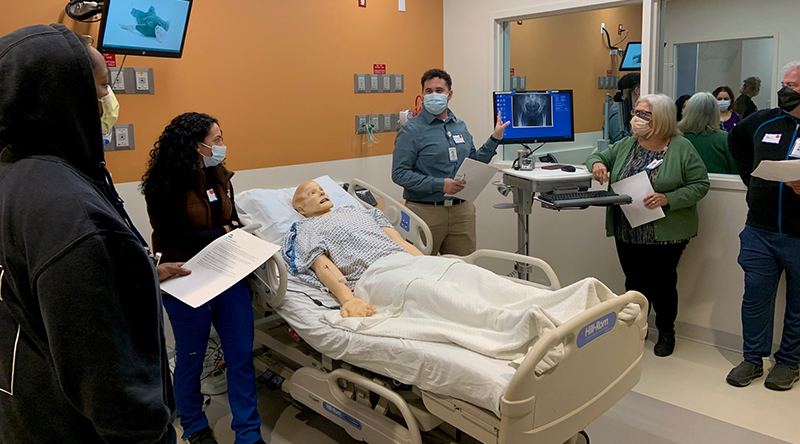

Christopher Cardona, quality assurance coordinator, Laboratory Services, YNHH (third from left), practiced giving corrective feedback during a recent simulation training for safety coaches.

Since Yale New Haven Health began its high reliability organization (HRO) journey in 2014, staff at each delivery network have received training on high reliability principles, behaviors and practices.

This training empowers staff to do their part to prevent errors and improve safety by using techniques embedded in the five CHAMP behaviors: Communicate clearly; Handoff effectively; Attention to detail; Mentor each other for 200% accountability; and Practice and accept a questioning attitude.

People request cross-checks and three-way repeat backs to watch out for one another and confirm verbal communications and tasks. We “stop the line” when clarity is needed in a situation, and to validate and verify that the correct patient is receiving the correct procedure, treatment or medication.

These skills and behaviors help us identify potential errors before they occur and harm reaches patients. To sustain a culture of safety and high reliability and keep safety at the forefront of care, we must practice HRO behaviors for every patient in every interaction.

That’s where safety coaches come in.

Safety coaches are employees who have received training on HRO CHAMP behaviors, highlight these behaviors in their departments and provide feedback to their team members to reinforce the use of these behaviors. Having safety coaches embedded within units and departments creates opportunities to review CHAMP behaviors in smaller, more personal work environments such as staff meetings and daily huddles.

“Safety coaches mentor and encourage others to speak up for safety through words and actions,” said Heather Buono, safety and quality specialist, YNHHS. “We’ve seen a substantial and sustained reduction in serious safety events since we began our HRO journey, and a large part of that is due to the safety coaches.”

To become a safety coach, staff learn how to observe daily practices; facilitate habit formation; gather and share safety stories; provide real-time feedback to peers; and communicate vital safety information and concerns. During hands-on training in the Yale Center for Medical Simulation, coaches practice giving and receiving both positive and corrective feedback under various conditions in different scenarios. Coaches at a recent simulation session said this helps them feel comfortable suggesting behavior changes to others.

“I welcomed the chance to better understand my role and share my insights with staff,” said Susan Cavanaugh, senior physical therapist, Long Ridge Medical Center, Greenwich Hospital, a safety coach for two years. “The training has empowered me to raise concerns when a situation warrants it, and I am hoping that I can empower others to speak up when they have a concern.”

“Coaches create a culture where everyone practices a questioning attitude,” said Eric Gilson, pharmacy technician, Central Pharmacy, Yale New Haven Hospital. “By deepening my understanding of CHAMP behaviors and how to utilize them, I hope to mentor my fellow technicians and help our health system get even closer to zero events of harm.”

The opportunity to share best practices with other YNHHS safety coaches is a valuable component of the training, said Andre McBean, quality assurance coordinator, Laboratory Medicine, YNHH. “Team effort is the best way to ensure we are all capable of supporting a safe environment – that we need to trust each other in making better and safer decisions,” he said.

Jasmine Jackson, specialty pharmacy liaison, YNHHS Outpatient Pharmacy Services (OPS), was eager to sign up for safety coach training. “I wanted to help not just our patients, but also help my colleagues better use CHAMP behaviors,” she said. “At OPS, it is critical to have clear communication to effectively hand off any situation. Attention to detail and holding each other accountable with a questioning attitude are what make us successful.”

The ultimate goal is for all clinical and nonclinical departments to have a safety coach.

“As CHAMP states, we should be mentoring each other for 200% accountability,” said Buono. “As safety coaches, we are, in effect, training staff to train each other. We all help each other to prevent mistakes and keep our patients safe.”

An upcoming safety coach simulation is scheduled for June 12 at the Yale Center for Medical Simulation. For details about becoming a safety coach, contact Heather Buono, [email protected].